Brian Alarcon

Subseedautopop

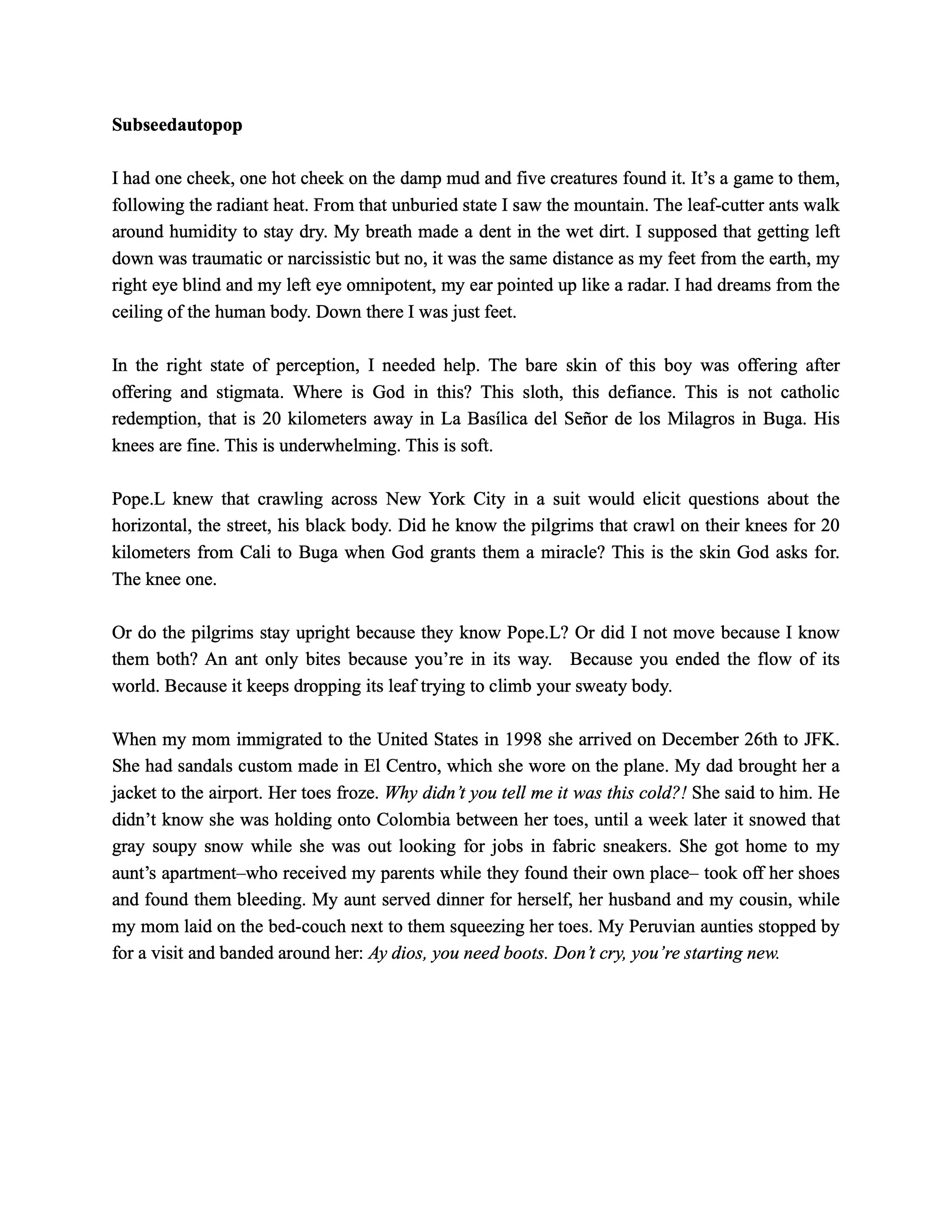

I had one cheek, one hot cheek on the damp mud and five creatures found it. It’s a game to them, following the radiant heat. From that unburied state I saw the mountain. The leaf-cutter ants walk around humidity to stay dry. My breath made a dent in the wet dirt. I supposed that getting left down was traumatic or narcissistic but no, it was the same distance as my feet from the earth, my right eye blind and my left eye omnipotent, my ear pointed up like a radar. I had dreams from the ceiling of the human body. Down there I was just feet.

In the right state of perception, I needed help. The bare skin of this boy was offering after offering and stigmata. Where is God in this? This sloth, this defiance. This is not catholic redemption, that is 20 kilometers away in La Basílica del Señor de los Milagros in Buga. His knees are fine. This is underwhelming. This is soft.

Pope.L knew that crawling across New York City in a suit would elicit questions about the horizontal, the street, his black body. Did he know the pilgrims that crawl on their knees for 20 kilometers from Cali to Buga when God grants them a miracle? This is the skin God asks for. The knee one.

Or do the pilgrims stay upright because they know Pope.L? Or did I not move because I know them both? An ant only bites because you’re in its way. Because you ended the flow of its world. Because it keeps dropping its leaf trying to climb your sweaty body.

When my mom immigrated to the United States in 1998 she arrived on December 26th to JFK. She had sandals custom made in El Centro, which she wore on the plane. My dad brought her a jacket to the airport. Her toes froze. Why didn’t you tell me it was this cold?! She said to him. He didn’t know she was holding onto Colombia between her toes, until a week later it snowed that gray soupy snow while she was out looking for jobs in fabric sneakers. She got home to my aunt’s apartment–who received my parents while they found their own place– took off her shoes and found them bleeding. My aunt served dinner for herself, her husband and my cousin, while my mom laid on the bed-couch next to them squeezing her toes. My Peruvian aunties stopped by for a visit and banded around her: Ay dios, you need boots. Don’t cry, you’re starting new.

El Pacífico Colombiano.

Have you eaten? It was the first time she had Peruvian food. She still remembers what she ate, yellow rice and chicken.

It’s not cruel to want to drop by the old farm my grandmother used to own in her hometown before my grandfather sold it to buy land where more mestizos live. It’s not even radical, that the family who took care of the land were in the conflict while we were post-conflict, visiting for weekends at a time. I hated going there as a kid, the banana crop scared me. Rows and rows of skinny trunks with large fronds creating dark hallways.

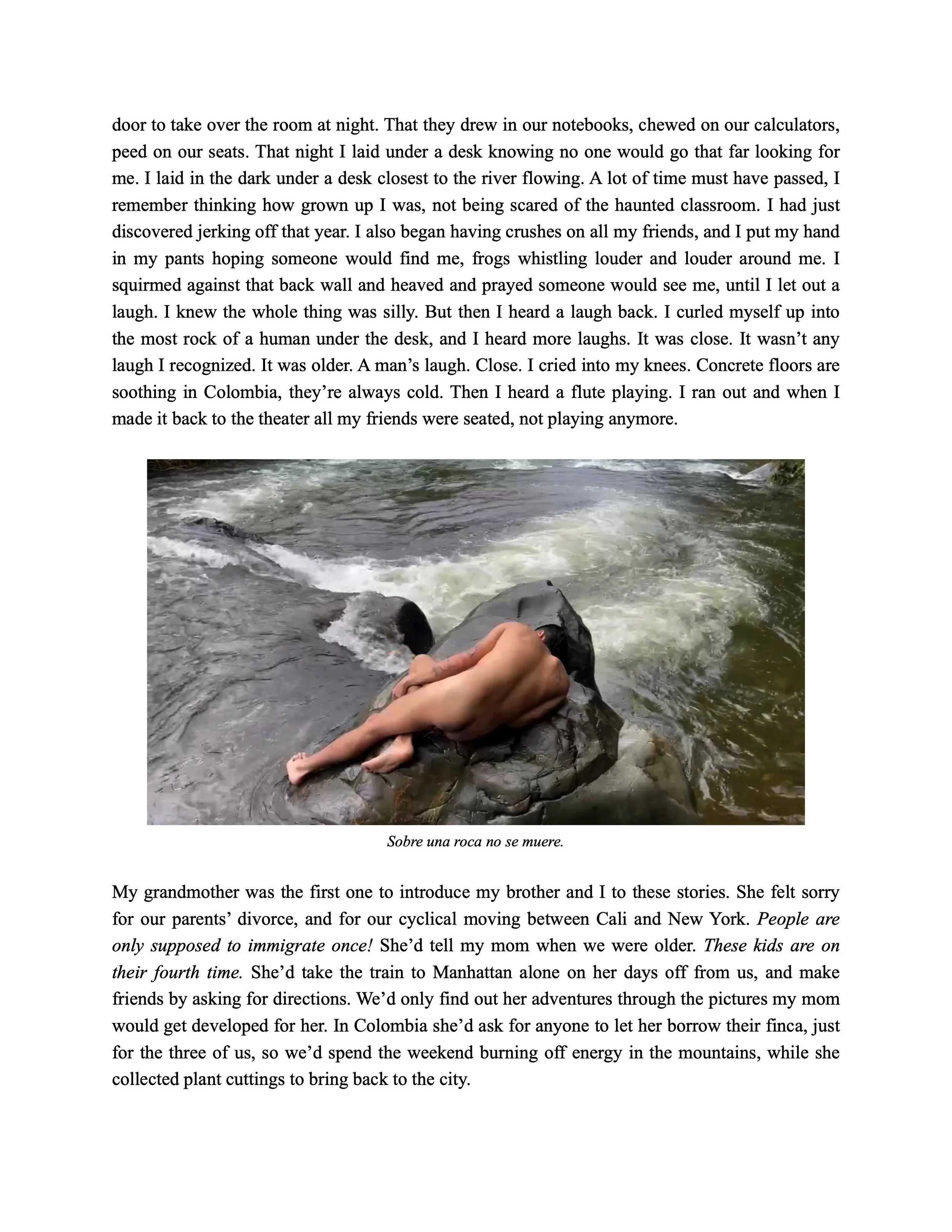

But there’s a great picture of me. My grandmother would stack rocks for us at the river to create pools. She’d make them so tall we could swim. I was always the quieter brother, or maybe it was a joke, but in the picture I’m floating still in the fetal position. Playing dead. Or maybe I was playing birth. Now no one will take me there because El Cauca is in conflict again. Again? Again. I think my family fears I’d make a good guerrillero.

Now when I lie down I do it to express myself. Unlike as a kid, when I used to measure myself with it. If I get flat enough, the wind can’t reach me. The entire world is the sky from down there. The hierarchy ends. Your head is as good as your feet. Your voice is a pipe. You can’t be seen.

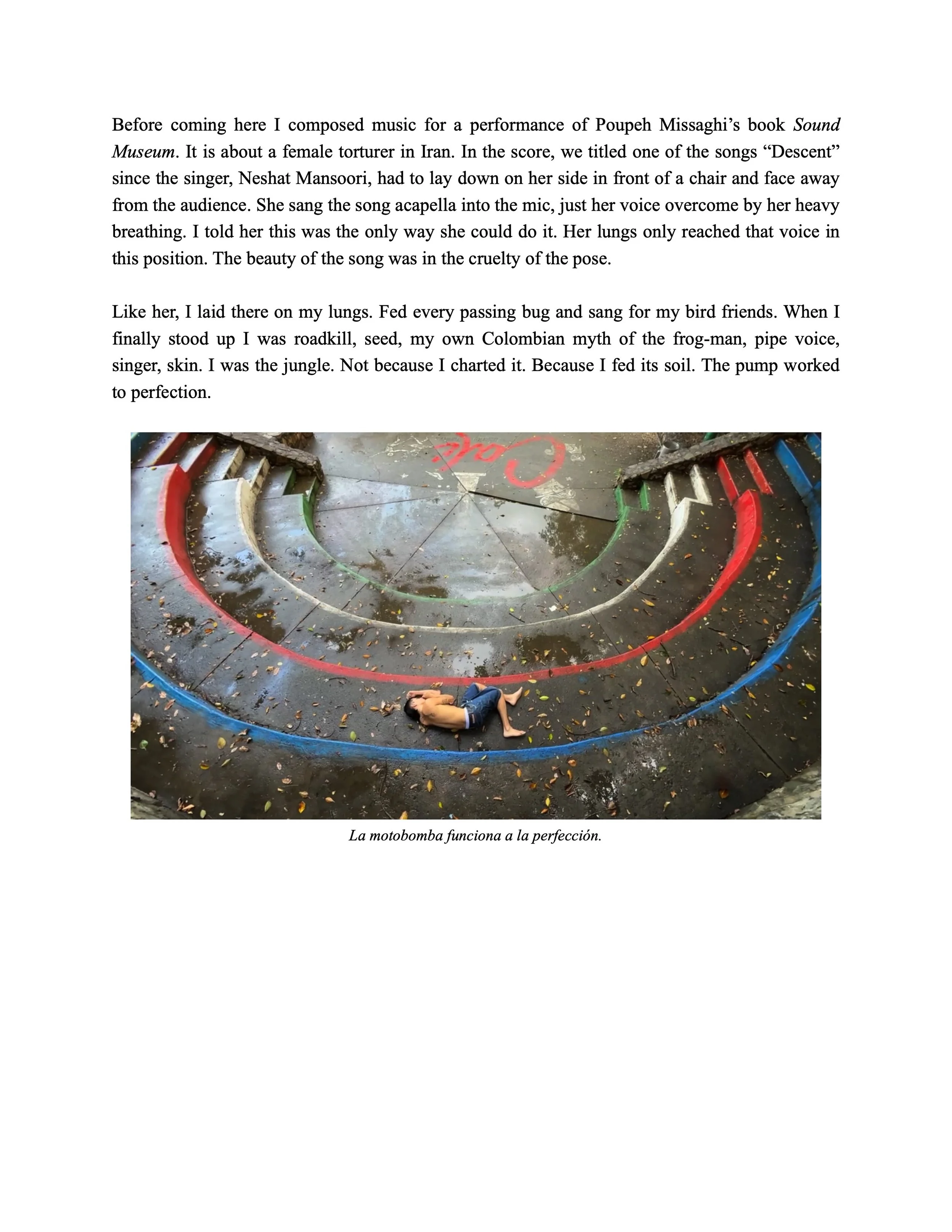

The pump works to perfection.

Pose

Hollow

Perfect

Noise

El Gran Diáfano

Silbando

dices

Un termino no más termino ni tan—

To say that lying down is anti-capitalist is to disregard all the work that can be done down here. I lay in bed to work. I can’t concentrate sitting in a chair. Chairs were made for us to be addicted to caffeine. I have ADHD. I’m either standing up or laying down. I can’t even drive.

I was 16 when I first tried weed. I ate too many edibles at a party. I went into the kitchen and laid down under the oven and closed my eyes. Apparently I screamed. My ex carried me up to the roof and threw me in the snow. I said I would never try weed again after that. Two weeks later I was smoking it. It became a secret with all our friends to never let him find out. We were the couple that always argued. I was tiring to be around. All because I laid down! I’d tell him.

All because I laid down; A chiguiro out of the dense trees visited me to taste something, his nose widening, my hands between my legs. With my tattoo markings I probably looked like a big, shitty frog. I’m not sure what it eats. At least to it I don’t look like a used up thing. If I tried to touch it it’d run, so instead I sang to let it know I’m venomous.

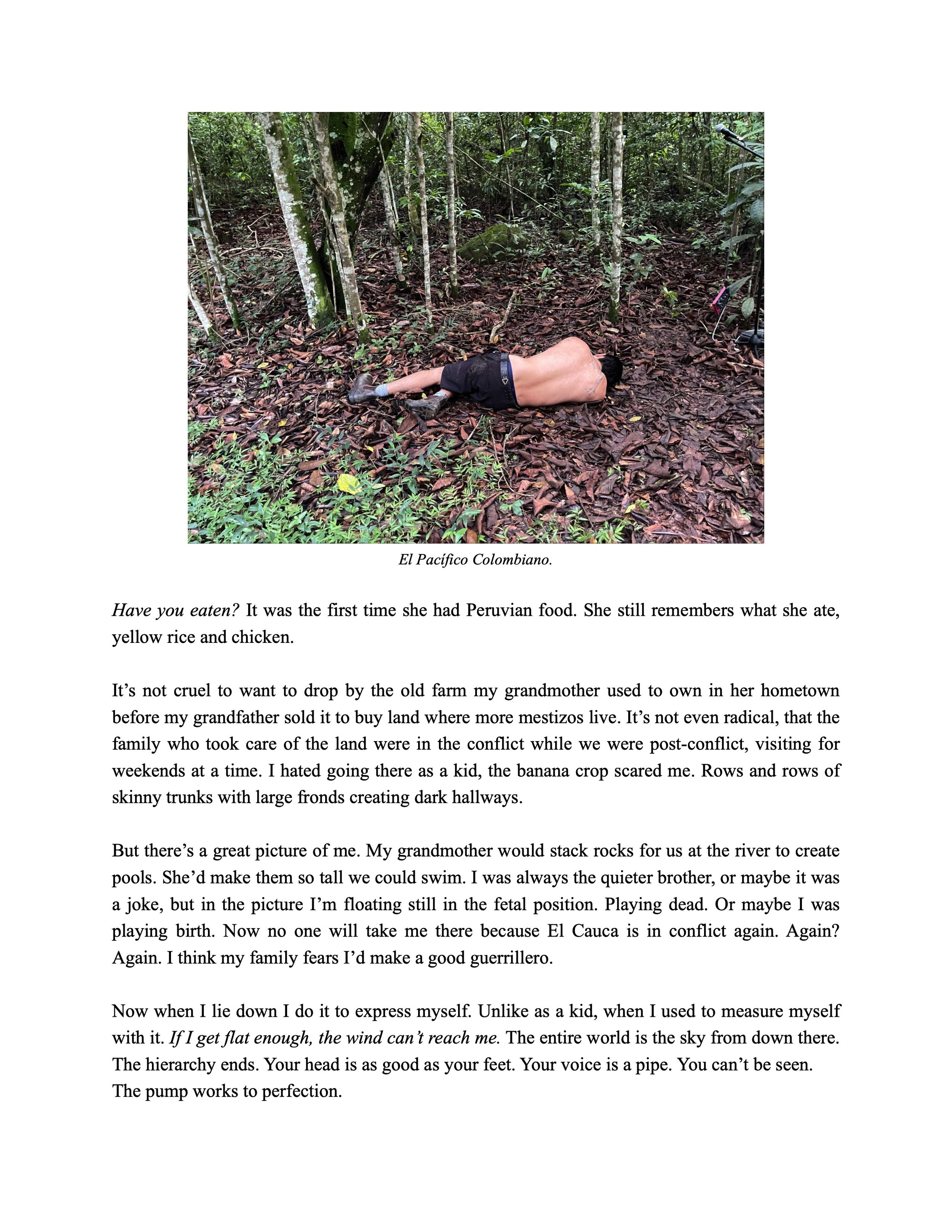

Tengo mis vicios.

Then, the birds. To them I do look like an end. There in the pacific jungle by myself humming. Wanting them.

But what could be so deadly about a body that belongs returning to its start? It’s not cruel. It’s the river to begin with. This river that has seen me grow has gotten cleaner with time. This month it took three people with it, their bodies in pieces finally getting caught downstream; heavy rains increased its power. The middle of it is impenetrable in the rainy season. In the dry season I’ve laid in its center and gotten knocked by a styrofoam cup. A cup that will outlive this river asking me to leave it.

In a part of it only accessible to fearless gay men, the river is wilder, unlandscaped, as it has always been. Though you do see men fucking between the trees, the river erodes the edges of the land creating curved cliffs around it. All roots and dirt. Here is where I go, men walking above me, not seeing me below, with my balls on the rocks, my legs in the stream, rolling and rolling in the hands of earth. Bugs that suck on me. A bird looking. Even the cliff scratches my back. Me vengo en él. After and after it is cold.

But I have been seen, lying like that. There’s the myth of El Duende, elves who terrorize rural places, braiding horses’ hair overnight. During a night event in middle school, my friends and I played hide and seek in my school’s open air “campestre” campus. Imagine 10 little boys running around the dark classrooms between tropical trees in burgundy suits. I hid in the most remote part of the school, the third grade classroom. It was a corner room with a creek flowing in from the wall behind it. When we were there, we used to say that the duendes used that river door to take over the room at night. That they drew in our notebooks, chewed on our calculators, peed on our seats. That night I laid under a desk knowing no one would go that far looking for me. I laid in the dark under a desk closest to the river flowing. A lot of time must have passed, I remember thinking how grown up I was, not being scared of the haunted classroom. I had just discovered jerking off that year. I also began having crushes on all my friends, and I put my hand in my pants hoping someone would find me, frogs whistling louder and louder around me. I squirmed against that back wall and heaved and prayed someone would see me, until I let out a laugh. I knew the whole thing was silly. But then I heard a laugh back. I curled myself up into the most rock of a human under the desk, and I heard more laughs. It was close. It wasn’t any laugh I recognized. It was older. A man’s laugh. Close. I cried into my knees. Concrete floors are soothing in Colombia, they’re always cold. Then I heard a flute playing. I ran out and when I made it back to the theater all my friends were seated, not playing anymore.

Sobre una roca no se muere.

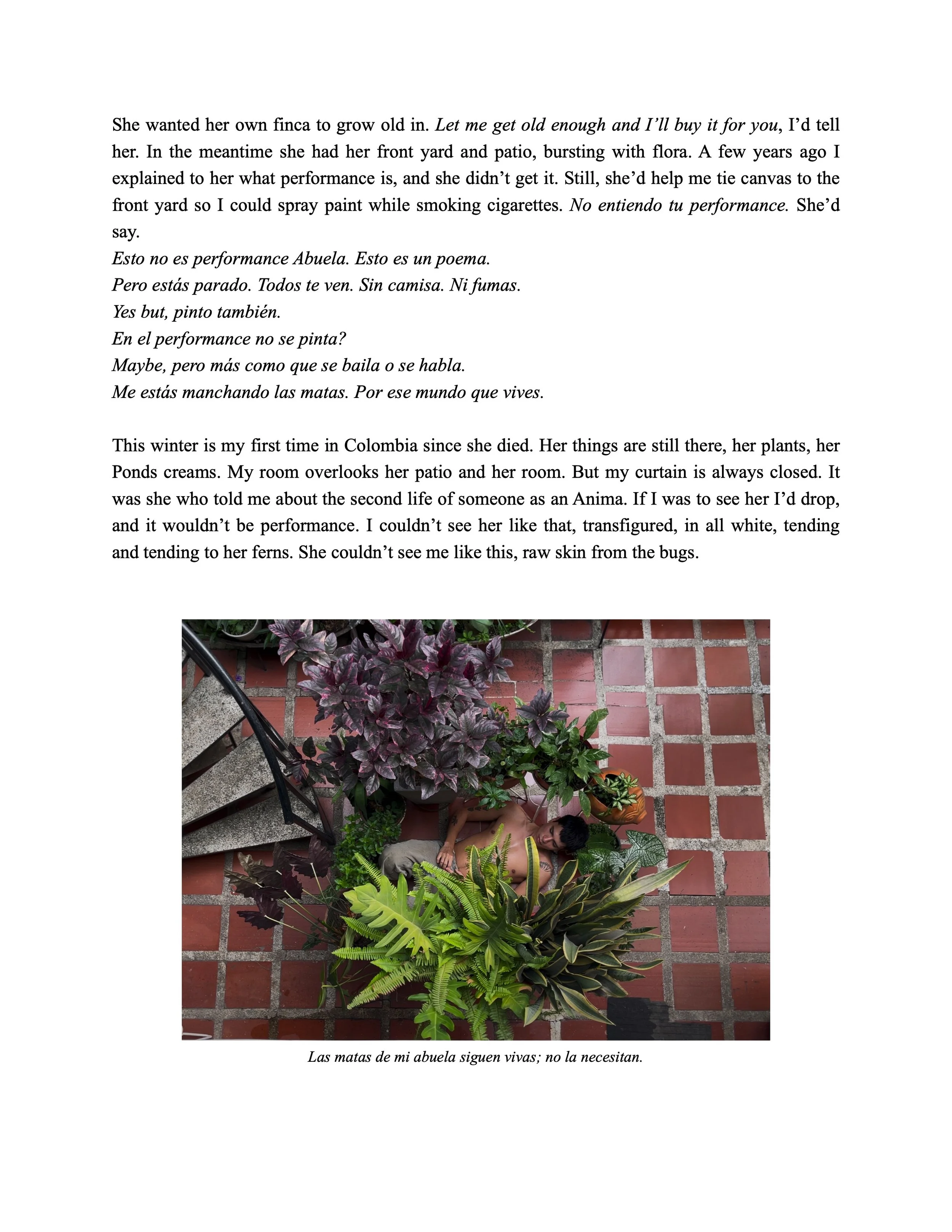

My grandmother was the first one to introduce my brother and I to these stories. She felt sorry for our parents’ divorce, and for our cyclical moving between Cali and New York. People are only supposed to immigrate once! She’d tell my mom when we were older. These kids are on their fourth time. She’d take the train to Manhattan alone on her days off from us, and make friends by asking for directions. We’d only find out her adventures through the pictures my mom would get developed for her. In Colombia she’d ask for anyone to let her borrow their finca, just for the three of us, so we’d spend the weekend burning off energy in the mountains, while she collected plant cuttings to bring back to the city.

She wanted her own finca to grow old in. Let me get old enough and I’ll buy it for you, I’d tell her. In the meantime she had her front yard and patio, bursting with flora. A few years ago I explained to her what performance is, and she didn’t get it. Still, she’d help me tie canvas to the front yard so I could spray paint while smoking cigarettes. No entiendo tu performance. She’d say.

Esto no es performance Abuela. Esto es un poema.

Pero estás parado. Todos te ven. Sin camisa. Ni fumas.

Yes but, pinto también.

En el performance no se pinta?

Maybe, pero más como que se baila o se habla.

Me estás manchando las matas. Por ese mundo que vives.

This winter is my first time in Colombia since she died. Her things are still there, her plants, her Ponds creams. My room overlooks her patio and her room. But my curtain is always closed. It was she who told me about the second life of someone as an Anima. If I was to see her I’d drop, and it wouldn’t be performance. I couldn’t see her like that, transfigured, in all white, tending and tending to her ferns. She couldn’t see me like this, raw skin from the bugs.

Las matas de mi abuela siguen vivas; no la necesitan.

Before coming here I composed music for a performance of Poupeh Missaghi’s book Sound Museum. It is about a female torturer in Iran. In the score, we titled one of the songs “Descent” since the singer, Neshat Mansoori, had to lay down on her side in front of a chair and face away from the audience. She sang the song acapella into the mic, just her voice overcome by her heavy breathing. I told her this was the only way she could do it. Her lungs only reached that voice in this position. The beauty of the song was in the cruelty of the pose.

Like her, I laid there on my lungs. Fed every passing bug and sang for my bird friends. When I finally stood up I was roadkill, seed, my own Colombian myth of the frog-man, pipe voice, singer, skin. I was the jungle. Not because I charted it. Because I fed its soil. The pump worked to perfection.

La motobomba funciona a la perfección.

Bio

Brian Alarcon is a Colombian-American poet, performance and visual artist from Queens, New York. His poetry crosses the borders between mediums and industries, having performed at art galleries, for media clients such as Versace and Drome Magazine, nonprofits like City Artists Corps and Counterpath Press, and he’s received fellowships from the Queer|Art Foundation and the Jack Kerouac School. His works have been published by The Columbia Review, Apogee Journal, Bombay Gin Literary Journal, among others.